The 8 worst slums of Victorian London

Date post added: 17th July 2023

Welcome to the slums of Victorian London

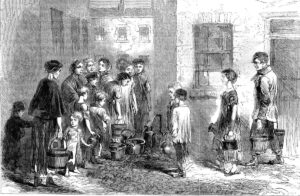

Dark, fetid, dangerous. Where poverty-stricken bodies crowd into poorly built tenements, or snatch a few hours of sleep in a doss house. Where open sewers trail through the slums, overflowing with bucket after bucket of slops. Where poverty and disease are rife and where infant mortality is shockingly high. Welcome to the slums of Victorian London in 19th century Britain.

From the most squalid areas of London to some of the most desirable

London’s East End was terra incognita to “the better sort” – British upper classes and middle classes. They just didn’t go there. They didn’t want to know about it. Ergo the blind eye they turned to the squalor and overcrowding and filth and crime the poor had to endure in “the worst slum in Europe” – and its outriders right across the richest city in Europe. It was only in the late 19th century, when the living conditions of the poorest in society could be denied no longer, that the slums of Victorian London began to be acknowledged, talked about and depicted in newspapers like the Illustrated London News. Eventually, of course, the slum areas were cleared, with many of these areas becoming some of the most desirable in London.

Today, we’re taking you back to the Victorian era and to the worst slums of Victorian London.

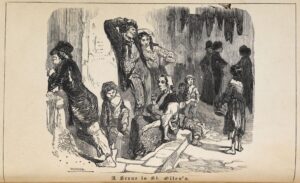

1. St Giles Rookery

One of the worst slums in Victorian London was in the West End, close to Covent Garden. In 1101, Henry I’s wife Matilda founded a leper hospital here in fields outside the city walls, hence the name St Giles-in-the-Fields. It was in the 18th century though that St Giles earned its reputation for squalor and ruin when artist William Hogarth created his famous work Gin Lane based on St Giles. Depicting life as it was in the heart of slumland, Gin Lane paints a picture of despair, neglect and poverty. And it only got worse. St Giles Rookery (rookery being a common term for slum housing) became lawless, filled with cadging houses and sordid dens, run by gangs and riddled with crime and prostitution. During the slum clearances, St Giles Rookery was cleared to make way for the New Oxford Street, joining Oxford Street and Holborn. Nothing of St Giles remains, but you can, however, join the Harlots & Bawds walk and delve into the real history of this notorious central London Victorian slum.

2. Devil’s Acre

Visiting majestic Westminster Abbey today, it’s hard to imagine that Westminster was home to one of the worst slums in Victorian London. But don’t take our word for it. Charles Dickens wrote about the area known as Devil’s Acre, debunking the notion that Westminster was a ‘city of palaces, or magnificent squares, and regal terraces’. Instead, wrote Dickens, ‘there is no district in London more filthy and disgusting, more steeped in villainy and guilt, than that on which every morning’s sun casts the sombre shadows of the Abbey’. It was in Devil’s Acre that Dickens visited The Ragged Dormitory and the Colonial Training School of Industry, a place where young vagrants and thieves could supposedly trade their crime-ridden past for an honest future. Some say that it was Dickens’ visits to the ‘Ragged School’ that inspired Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol. With a spell as an Irish rookery, Devil’s Acre was a place where pickpockets, thieves, prostitutes and sharpers converged. Want to explore one of London’s worst Victorian slums – see Devil’s Acre, hear about it, get a feel for it – here’s the walk.

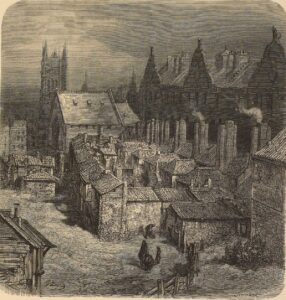

3. Whitechapel

Home to many of London’s poor, from the working classes right down to the destitute, Whitechapel was plagued by overcrowding, crime and deprivation. The Charles Booth poverty map of the late 19th century showed this clearly, colouring huge swathes of Whitechapel black (‘lowest class, vicious, semi-criminals’) dark blue (‘very poor’) or light blue (‘poor’). Lodging houses were created to shelter the homeless overnight, with minimal facilities – often not even privies. But, as more bodies were packed in, conditions were abysmal and many chose instead to walk the streets. And of course, it was the East End alleyways of Whitechapel that Jack the Ripper stalked, searching for his next victim.

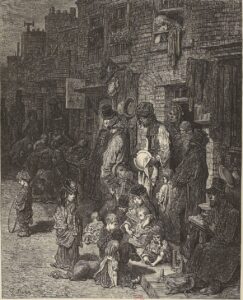

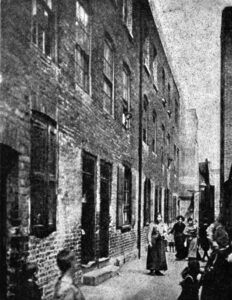

4. Frying pan alley

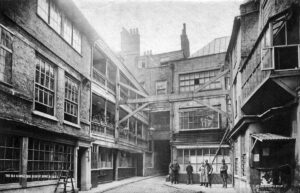

Jack London was a 26-year-old American journalist whose interest was roused by the plight of the poor. In the 19th century, many of the world’s cities, like New York, were blighted by slum housing. From a poor background himself, Jack became fascinated by London’s East End. He spent weeks exploring the poorest parts of London, sleeping in workhouses, experiencing Victorian London slum living conditions first-hand, and pouring it all into his book The People of the Abyss. One such story is Jack’s visit to a ‘sweating den’ in Frying Pan Alley, Spitalfields. He describes walking on its ‘slimy pavement’ and into an ‘abomination’ of a house, up a narrow and foul stairway ‘heaped with filth and refuse.’ Jack was greeted with tiny rooms, each with a large desk taking up most of the space, and 20 people crammed around it, surrounded by the detritus of shoemaking. In another room, a young boy lay dying of consumption. From the window, Jack recalls the ‘one storey hovels’ where people lived, roofs covered in filth, fish and meat bones and the ‘general refuse of a human sty’. Frying Pan Alley still exists to this day, although you’ll find it much changed from the Victorian times. Get an expert tour on the Immigration & Food Walk.

5. Jacob’s Island, Bermondsey

Located on the south bank of the Thames, the rather glorious sounding Jacob’s Island was anything but. Jacob’s Island was another of the Victorian London slums that caught the attention of Charles Dickens. He chose it as the spot for Bill Sykes to meet his end. Set beside the polluted River Neckinger, ‘the very capital of cholera’, Jacob’s Island was a notorious rookery. It was to the Bermondsey slums that journalist Henry Mayhew was despatched in 1849 to report on a cholera outbreak. Author of London Labour and the London Poor, Mayhew conducted first-person interviews with London’s poorest. This area was bombed extensively in World War II – 19th century slum clearance compliments of the 20th century Luftwaffe! But there’s still trace evidence – the outlines of Jacob’s Island and even the feel of Jacob’s Island. If you know where to go and where to look – and we do on our Undiscovered London, Shad Thames, Butler’s Wharf walk.

6. Bethnal Green

Earning a mention in George Sims’s book How The Poor Live and Horrible London, Bethnal Green was the poorest area of London in Victorian times and a known rookery. Old Nichol Street was particularly squalid, with the lowest class housing consisting of tenements with walls running with damp. In 1889, Charles Booth found that 45% of the Bethnal Green population lived below the basic subsistence level – the highest percentage in London. The slum clearances, of course, completely transformed Bethnal Green but if you know where to look – if you’re lucky enough to be shown round by guide Steve Fallon, author of The Lonely Planet Guide to London – there are any number of clues to this area’s fascinating slumland past! Steve’s walk starts at Bethnal Green Tube.

7. Notting Hill Potteries and Piggeries

Today, Notting Hill is one of London’s most desirable addresses, but in Queen Victoria’s time, it was awash with filth. Described by Dickens as ‘a plague spot scarcely equalled for its insalubrity by any other in London’, the Potteries and Piggeries (formerly known as Cut-throat Lane) earned its name when pig keepers and rowdy brick makers moved into the area. Slum dwellers slept in their hovels, alongside their animals, lacking even basic sanitation. It was in Notting Hill that Peter Rachman, a notorious provider of slum housing, owned properties. Synonymous with poor housing ‘Rachmanism’ became a term for landlords exploiting tenants with slum housing. If you’re visiting, look out for the last remaining brick-making kiln on Walmer Road, just north of Pottery Lane. For the Potteries and Piggeries and much more besides, try the Notting Hill & Portobello Market walk.

8. Southwark

Just south of the Thames, Southwark still bears the scars of its furtive, villainous, 19th century past. There are sites from the paupers’ burying ground and a ragged school to the prison that marked Charles Dickens for life, and inevitably found its way into his fiction. Taking its name from South Warke or Work, Southwark was a melting pot of London’s poorest souls. It was home to the chimney sweeps and the prostitutes, the soon-to-be-executed Black Maria, the pickpockets and the street sellers. Then, of course, there was the body snatching gang. The St. Saviour’s Union Workhouse on Mint Street is believed to have been yet another source of inspiration for the works of Charles Dickens. The Lancet describes the women’s ward of the workhouse as ‘a miserable room, foul and dirty’, ‘the floor being simply bedded with straw’ and a ‘den or horrors’. To hear what it was really like in the slums of Southwark, the walking tour Darkest Victorian London will transport you back in time.

For a 21st century perspective on the 19th century horrors of Victorian London, join us on the Sorting the slums of Victorian London tour. Don’t worry, we won’t make you endure privies and open sewers, we’ll point out better facilities en route.