Why is Jack the Ripper still talked about today?

Date post added: 15th October 2023

There’s a contemporary obsession with true crime that holds endless fascination for people. From podcasts to novels to period BBC dramas, the crime genre is incredibly popular. But fact can be stranger than fiction, and the ‘true’ historic tale of the infamous serial killer, Jack the Ripper continues to be a conversation point. Hence our ever popular Jack the Ripper walk which will transport you back to where it all began in 19th century East London.

How did Jack The Ripper avoid getting caught?

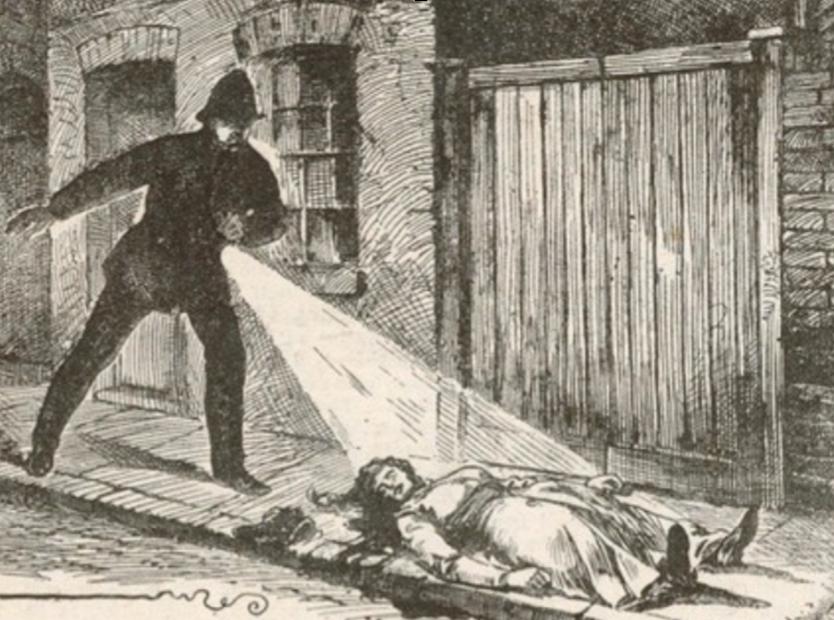

Jack the Ripper. The perpetrator of the grisliest, unsolved crimes in British history. Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror over the narrow East End alleyways of Spitalfields and Whitechapel continues to fascinate people to this day. Believed to have committed at least five gruesome murders between August and November 1888, Jack the Ripper preyed on down and out women in the Whitechapel district. And concomitantly he in a sense preyed on Scotland Yard and the City of London Police – because time and again he slipped their nets. The police force was never able to catch him.

The Ripper’s victims – Mary Ann Nicholls, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride, Catherine Eddowes and Mary Jane Kelly – are known as the canonical five, but some Ripperologists believe that the true extent of the notorious serial killer’s rampage may have been far more extensive. Indeed, a police file called The Whitechapel Murders details the 11 women who were murdered on London’s streets between April 1888 and February 1891. Despite macabre clues left at the crime scene, the identity of Jack the Ripper – the primal, prototype serial killer – was never uncovered.

Today, with the help of renowned crime historian and London Walks guide Donald Rumbelow and Blue Badge guides, Ripper experts and London Walks stalwarts Delianne Forget and Richard Walker, we delve into the question, why was Jack the Ripper never caught?

The conditions of 19th century Victorian Britain

Among the main challenges for police officers investigating the Jack the Ripper murders were the conditions in the East End of London at the time. In Spitalfields, the centre of the Ripper murders, there was gross overcrowding. In London as a whole, there were 50 people per acre. In Spitalfields, this number rose to an astonishing 800 people per acre. Slums were being cleared, new businesses were being created, all forcing people into smaller and ever more cramped lodgings. People slept seven, eight or nine to a room. In the casual lodging houses, up to 80 people were crammed together into one dormitory. In this foetid landscape, lit only with dim gaslights, a serial killer could lurk unnoticed, mingling with the crowds. And it was into this unsanitary, overcrowded environment that many Jewish refugees sought safety having fled the pogroms in Eastern Europe.

The lack of forensic science

With our modern day knowledge of forensic science and DNA evidence, it can be hard to imagine the difficulties of the Ripper police investigation. Fingerprinting, for example, was known but not used in policing until the first fingerprint-generated conviction in 1905. Blood grouping wasn’t known at all, meaning that forensic evidence left at the scenes of the murders was a closed book. Detectives were simply unable to investigate it, to “read it”, the way they would be able to today.

One of the most chilling of all the Ripper murders was that of Catherine Eddowes. Her body was discovered in Mitre Square, near the eastern boundary of the City of London. Her throat had been slashed. She’d been disembowelled. Her face was disfigured. Jack the Ripper also took Catherine’s uterus and left kidney as horrific mementoes of his deed. This grisly act became part of the notorious serial killer’s modus operandi.

A recent, much disputed “development” in the case has focused on a blood-spattered shawl, said to have been taken from the scene of Catherine Eddowes’ murder in September 1888. It was purchased at auction by Russell Edwards, a man who used DNA analysis to link the shawl to Polish immigrant Aaron Kosminski. The shawl was later analysed by Dr Jari Louhelainen of Liverpool John Moores University in 2011, who found evidence of split body parts consistent with human kidney removal. Louhelainen also found that mitochondrial DNA taken from the shawl matched that of direct descendants of both Catherine Eddowes and Aaron Kosminski. Well, that’s the contention. Other Ripperologists say it’s nonsense. Yet another Jack the Ripper wild goose chase.

Murder was uncommon

A key reason that the Ripper was never caught is a simple one – murder was still uncommon during the reign of Queen Victoria. In the Metropolitan Police area, there were 13 murders in 1887, 28 in 1888 and 17 in 1889. With murder being uncommon, murder investigations were too, but contrary to popular myth, there was a tremendous amount of support for the police force during their quest to uncover Jack the Ripper’s identity. It was only the hostility of W.T Stead, the Editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, that caused so many problems. Stead had a personal axe to grind, seeing himself as the champion of the working classes following the rough handling of the Bloody Sunday riots of 1886 by the police. Footnote: Stead’s own end was the stuff of history books: he went down with the Titanic.

They were prisoners of Victorian prejudice

The true identity of Jack the Ripper may never have been uncovered due to Victorian prejudice, which was most clearly seen with the ‘Macnaghten Memoranda’. Sir Melville Lesley Macnaghten was the Assistant Chief Constable of Scotland Yard’s CID from June 1889 to December 1890, some 6 months after the last of the Ripper murders took place. The memoranda, intended to be an internal document, was written by Macnaghten suggesting three potential Ripper suspects, Montague Druitt, Aaron Kosminski and Michael Ostrog, all linked to common police prejudices at the time.

Macnaghten suggested Montague, citing he was “a doctor & of good family” and “sexually insane”. The police didn’t want to be outwitted by someone “sexually insane” in this most career-damaging set of crimes. Gay men were, at the time, regarded as mentally unstable as demonstrated in Psychopathia Sexualis published in 1886, then regarded as the standard work on homosexual criminal behaviour. Kosminski was named for being “a Polish Jew” and “insane owing to many years indulgence in solitary vices.” The last suspect named by Macnaghten was Ostrog, “a convict, who was subsequently detained in a lunatic asylum as a homicidal maniac.” Police at the time regarded serial killing as a crime like any other.

A hoax from hell

Some say that the first time Jack the Ripper struck was not when he murdered Mary Ann Nichols, known as Polly, but earlier, the slaying of Martha Tabram on 7th August 1888. What is clear, however, is that public interest around the murders was intense, with the Daily Telegraph and The Times carrying transcripts of the Ripper victim inquests. The police received many letters said to be written by the murderer but only two revealing facts about the case not within the public domain and claiming their name was Jack the Ripper – the moniker by which the murderer would become known. The most horrific of the letters though was that received by George Lusk, head of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee on October 16th 1888 containing half a human kidney. Lacking modern crime detection techniques, the police were unable to tell whether the letters were authentic or chilling hoaxes. In consequence, the letters may well have muddied the waters. Finding out who Jack the Ripper was was never going to be easy. The difficulties the English police faced were compounded by false leads, looking in the wrong place, the trail going cold. Hoaxes abounded for years, even one linking Queen Victoria’s grandson Prince Albert Victor to the case.

The journey to the Autumn of Terror

With the benefit of hindsight – looking back at the evidence – it is easy enough to understand why the police failed in their attempt to catch Jack the Ripper and bring him to justice. What is also clear is that the grisly story of “the autumn of terror” – and its “From Hell, Sir” protagonist Jack the Ripper – has held us in thrall for well over a century. But you know something, there has been a breakthrough in our time. We are still largely in the dark about who Jack the Ripper was but we are no longer in the dark about his victims. We no longer see them as bit-part players – “lowest of the low, down and out prostitutes.” If there is a measure of justice it’s because recent investigations, now incorporated into the London Walks journey into the Autumn of Terror in the East End of London, have brought the murdered women into the foreground, seen them whole, understood their plight, respected them as human beings.

The Jack the Ripper story is the infamous, unsolved British crime – but it’s also the story of five women who need to be rescued, in memory, from the evil shadow that psychopath cast over them. This East London walk does that.