Londons Quackery and Fake Doctors

Date post added: 18th May 2023

The Chambers dictionary definition says that a quack is ‘someone who claims, and practises under the pretence of having, knowledge and skill that he or she does not possess.’ Basically, quack doctors are a fraud. Somebody who pretends to have medical skills and credentials that they don’t possess.

The term ‘quack’ evolved from the old Dutch term ‘quacksalver’ which now translates as ‘kwakzalver.’ It has nothing to do with ducks as you may have presumed.

When did quack doctors practice in London?

There are references to Italian style quacks or mountebanks (literally translated to ‘he who jumps on a bench’) performing charlatan acts of medical falsehood back in Renaissance Venice.

In England, there was a rise in quackery in the 16th and 17th century because healthcare was removed from the responsibility of the church in 1533 when Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries. Without the church as regulators, ordinary individuals could set themselves up as freelance medical practitioners.

It was not illegal to practice as a quack and they even had their own coffee house, The Rainbow in Fleet Street. They diminished in number during the 18th century when regulators made it increasingly important to show qualifications as a doctor.

In the late 19th century, journalist Adolphe Smith wrote articles in Street Life in London depicting the daily sights in the capital city. One entry mentions,

“Street vendors of pills, potions, and quack nostrums are not quite so numerous as they were in former days.”

So they weren’t as prolific in the 19th century as in the 17th century, but they still existed.

We may think that this practice is confined to olden times. Think of the NHS and advancements in modern medicine. But if you spend long enough online, you’ll find a host of unregulated health practitioners wielding pills and potions as cure alls for today’s so called afflictions – diet pills, anti-ageing potions, hair thickening mixtures and the list goes on. In fact, check your junk emails to find a host of quack medicine spamming your inbox.

What is an example of medical quackery?

Purported cures were known as patent medicines. There were patent medicines touted to cure all known diseases or a specific illness or condition.

Dr Solomon claimed that his Cordial Balm of Gilead would cure anything, with particular efficacy on venereal diseases. It was brandy mixed with some herbs. Dr Sibley’s tincture claimed to bring someone back to life after death!

Plenty of quacks offered cures for common 17th century epidemics like cholera and plague. Many of these were herbal tinctures containing the likes of opium, quinine or digitalis, but some of them were just any old stuff.

What is the difference between a quack and a charlatan?

A quack considers himself to be a real doctor and not a fraud. A charlatan is consciously trying to hoodwink the public by posing as a physic.

Who was a famous quack doctor?

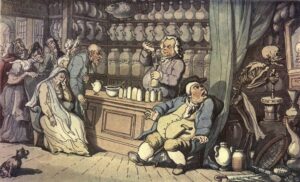

In the 17th century, various quack doctors were portrayed in paintings, namely Jan Steen and Jan Victors who performed in the 1650s. Take a look at William Hogarth’s artwork, depicting scenes of quack medicine, such as Marriage à-la-mode: The Visit to the Quack Doctor, 1743.

But one of the best-known quacks, if only because of his elaborate tomb in Southwark Cathedral which he himself paid for, is Lionel Lockyer (1600-1672).

In 1660, Lockyer claimed to have trapped the sun’s rays in a pill. The Pilula Radiis Solis Extracta (in Latin) sold widely, throughout London, Great Britain and to overseas colonies.

Lockyer claimed the pill would treat leprosy, fever, headache, gout, dropsy, palsy, convulsion fits, constipation, coughing, worms, phthisic (tuberculosis), scurvy, jaundice black and yellow, rickets, the King’s Evil or scrofula, gonorrhoea, green sickness, fistula, cancer and haemorrhoids and the list goes on.

The pill’s success made Lockyer a wealthy man. When he died, he was able to give £50 (equivalent to about £5,000 today) to 200 poor families in Southwark, a gold mourning ring worth seven shillings to 200 friends and £1 to anyone who turned up at his funeral. Unsurprisingly, there was quite a crowd in attendance (a ‘rent-a-crowd’). These generous gifts were in addition to the substantial cost of the memorial.

Some may call Lockyer a charlatan, but he and his customers would deny that vehemently. He studied alchemy in Germany, but never took any exams. It didn’t equip him to be a physician, surgeon or apothecary, but it helped with his quackery.

Picture the time in which he was operating. The time of plague. Medical practitioners weren’t able to halt the spread of infection or cure the disease, so people turned to the quacks selling their remedies on the streets for a cheaper price. There are many success stories with people praising Lockyer’s treatment of their diseases from cancer to worms. In fact one woman claimed that he rid her of 500 worms in five hours (too much information?).

Discover more of these grisly and fascinating stories in animated detail on our Quack Doctor’s guided tour